Features

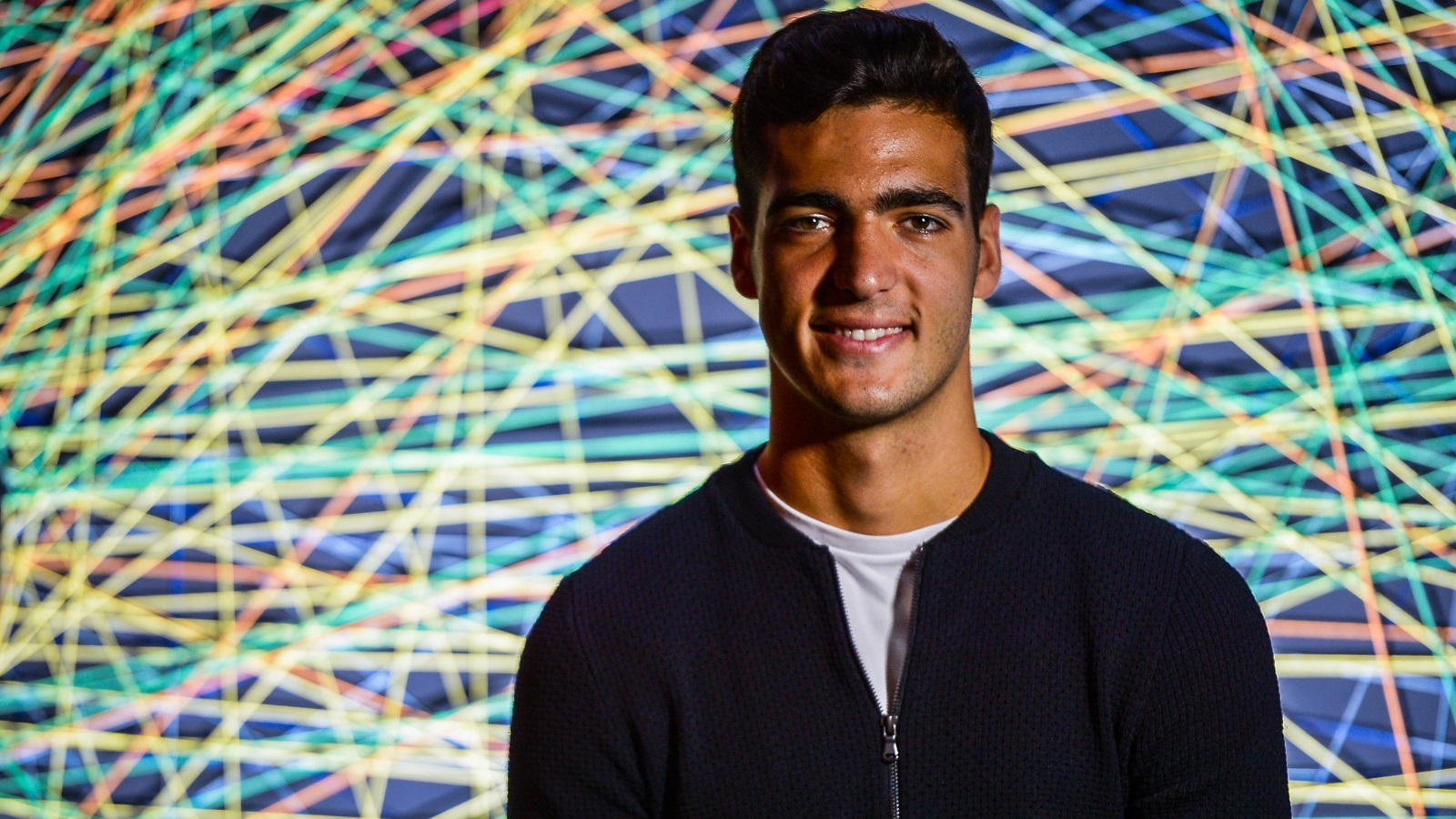

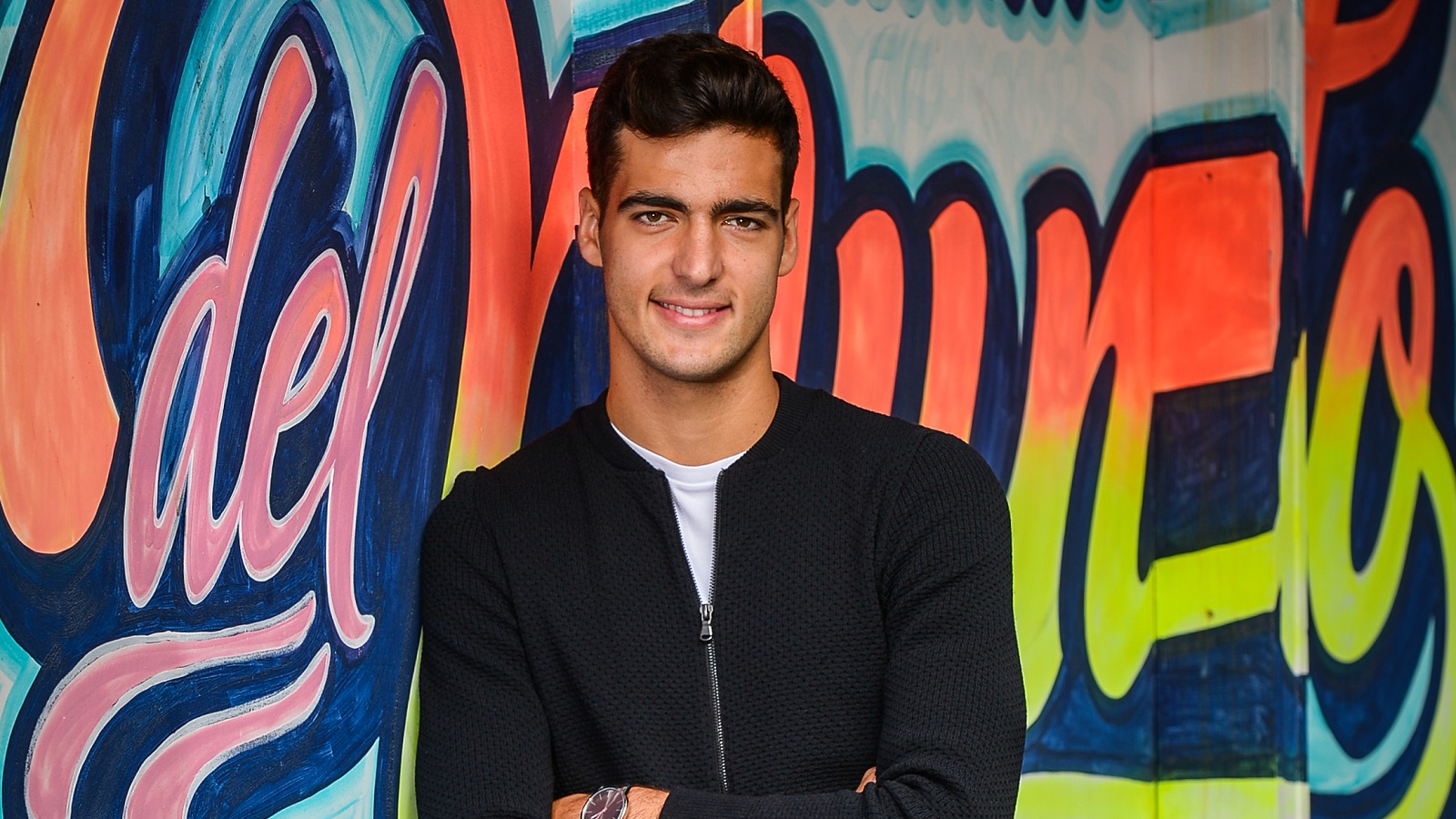

Mikel Merino programme interview - in full

Written by Tom Easterby

Mikel Merino has taken to English football with such effortless grace you’d think he’d been orchestrating Premier League midfields for years. This week, the 21-year-old met United for an exclusive interview, where he spoke about growing up in Spain, dealing with criticism and going toe-to-toe with one of the finest midfielders of his time. It was published in Saturday’s issue, and now you can read it in its entirety here…

Around 250 miles north east of the Spanish capital Madrid lies Pamplona, a small city home to just under 200,000 people. It is the birthplace of a handful of Premier League players, such as Fernando Llorente, César Azpilicueta and Nacho Monreal. Another of its famous sons, Mikel Merino, smiles as he explains what his hometown is better known for.

“Pamplona has a party in summer, called San Fermín. In San Fermín, every day during the week, on the mornings, there is a run, where the bulls run and the people run in front of them,” says the 21-year-old of the festival pursuit known as the encierro, or the Running of the Bulls.

“You wake up at seven and then you go to see the run. It’s dangerous, but it’s a normal thing there. During all the history there it has always happened, and it will continue. Nobody thinks about the dangers – it’s just normal there.”

Merino, the most eye-catching of Newcastle United’s summer acquisitions thus far, spent seven years in the city during a childhood which also saw him follow his father Ángel, a professional footballer, to places like Las Palmas and Vigo.

Kicking a ball about with friends between classes in Pamplona provide some of his clearest childhood memories. “Those matches were like the Champions League final for us, it was crazy, the intensity,” he laughs. “Later, my mother always said bad things because all my clothes were dirty, with grass on them and everything. They’re the first things in my mind when it comes to playing football.”

But Merino shakes his head at the question of whether his father’s job gave rise to his own love of the sport. “No – he never wanted to force me to do it. My mother told him ‘we’re not going to buy him a ball – if he wants one, then maybe we will get him one’. But then I started stealing balls from other kids, and then they said, ‘OK, it’s time to buy him his own ball!’

“When I was young, my parents never told me to do it, but when I was a little bit older I started asking my father, ‘why do we do this like this? When I’m here, what do I have to do?’ If I asked, he would respond to me.

“I was too young to see him play, but I’ve seen some videos about him – his best plays, some matches and goals of his. He was really versatile, he could play in a lot of positions. His main position was midfield, but he could play as winger, number ten, number eight, number six – more or less like me. He’s been a great mentor. I learn from his advice.”

From his son’s words, it is difficult to overstate Merino senior’s influence in helping the Borussia Dortmund loanee become the rounded, elegant midfielder he has proved to be in his first month at St. James’ Park. Ángel formally coached Mikel just the once, though, while the pair were trainer and player in the Osasuna youth ranks.

“It was strange, it was really, really strange. I was used to looking at him as my father, in my house, where there is love, and we can say stupid things,” recalls Merino. “And then this was the serious part of my father – training, with the respect of all the other guys. I was like, ‘where am I?’”

Merino left Osasuna, and all his home comforts, behind when he moved to the Bundesliga with Dortmund, in July 2016. “You start learning, it’s a new experience, but there’s so much difference in your life, culture, the weather. Everything is different. It’s a big step – not only in my professional career, but in my life,” he says.

“It is incredible, the level (the Dortmund players) are at – the rhythm, their pace, their strengths, everything. They don’t make mistakes. I learned a lot from that year.

“I had a really good relationship with all my teammates. I thought that, at that level, the people would be a bit chest-out, a little bit…” Merino gestures, implying arrogance. “But they are really, really humble. It was incredible to live that.

“I played with Gonzalo Castro, Marco Reus, Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang, and when I played against Bayern Munich, I played against Xabi Alonso, Thiago… It was crazy. You see the ball one metre from you, but you can’t take it because they are so good.”

Merino played just nine games for Dortmund in a tough first year at the Westfalenstadion. He picks out the experience of playing against World Cup winner Alonso – a player who Rafa Benítez brought into English football – as particularly memorable. “He is in the same position as me, but the way he plays – it’s too easy. He plays while walking. You are at 100 per cent, but you can do nothing. It’s incredible to live that. I’m really happy, because that will be helpful for the future.”

Alonso is a neat link who connects Benítez, his manager at Liverpool, to his countryman Merino, who has been fulfilling a similarly influential role in the middle of the park in recent weeks.

Alongside the classiness in possession, a trait both players share, there is also a certain durability about the pair. There exists a lazy stereotype in the English game, which dictates the more technically-gifted imports are less likely to savour the more rugged aspects of the sport; the running, the so-called dirty work.

But Merino has displayed a willingness to put a foot in during his early days on Tyneside. “It’s part of me, and it’s the way I understand football. You can be a really good player on the ball, but you have to compete yourself,” he says. “You have to fight for the ball, defend, run. I love running. If I finish a match and I’m not exhausted, that means I haven’t given 100 per cent, and that would be wrong.

“You have to go onto the grass and compete, not only have the ball and do tiki-taka, like they say in Spain. You have to be complete, and get better and better. If you only think about having the ball, you will not be as good as if you work on all parts of your football.”

It was suggested by some that Merino may have some work to do following his first Premier League start in the 1-0 defeat at Huddersfield. He was scolded post-match by former United manager Graeme Souness, observing from his Sky Sports studio vantage.

“I heard something about the words he said, but I don’t give importance to it,” he says. “I know that people will talk, that’s part of this, and maybe someone doesn’t like you. You know that, and you just have to keep on working like you are doing.

“When I finished that match I was not happy with the result, but I thought the team did a good job. I’m pretty sure that if you play exactly the same game and win, people would go, ‘good job, good player’. If you lose, things change.

“But the important thing is that we, the players, know that and we’re focused on ourselves.”

Six days later, Merino starred on his first start at St. James’. “It’s part of football. It’s part of being intelligent, being clever, being calm and knowing how it works. Maybe if I was a bit angry or disappointed because of people saying things, I wouldn’t have played the same way. So I tried to do my job, enjoy playing and helping my teammates, and…” He grins. “Well, we won 3-0.

“I received the love of the fans on social media and I’m so thankful for that. I love when people say you are good, but I take it easy, because it can change. I love the way people are with the team, the way people support the team in the matches, it’s the perfect way – the combination between the team and the crowd is incredible, and it has to be like this to improve.”

As his Instagram stories have shown, Merino has spent some of his free time finding restaurants, bars and beaches to visit near his new home. “I went to Alnwick too, to the castle to see it. I love to find new places,” he says.

But the real challenge for the promising Spaniard lies not in adapting to a new city, but in turning the early promise into consistent displays of quality. He faces constant competition for his place – particularly from Jonjo Shelvey, a player of similar talents who Merino describes as “one of the best players we have”.

As a loanee, he is effectively playing for a permanent home. Merino, a thoughtful young man who exudes a maturity far beyond his years, does not seem like one to let the burden of expectation sit heavy on his shoulders.

“Normally, I don’t feel the pressure. I’m lucky I’m like that,” he says. “But I need to improve myself, I have this year to try to get better, and help the team to get better too.

“I feel no pressure to make an impact. If I work hard, do the right things and have the right mentality, the right things will come.”

"I received the love of the fans on social media and I’m so thankful for that. I love when people say you are good, but I take it easy, because it can change. I love the way people are with the team, the way people support the team in the matches, it’s the perfect way – the combination between the team and the crowd is incredible, and it has to be like this to improve."