Features

Long read: Tony Lormor's story

Written by Tom Easterby

“Ask me anything. Nothing’s off limits. Feel free to ask me anything. It doesn’t need to come out, but I want it to come out so that people understand it.”

At the end of 2014, Tony Lormor gathered his thoughts. “After the first time, I remember sitting down with a piece of paper,” he explains. “My writing had completely changed.

“I literally sat down, and wrote ‘I want to try and change the world’. I thought if I could change myself, then I could maybe help as many people as I possibly could. I tried to continue that all the way through. I had some really dark days, with alcohol and depression and things like that.

“But when I finished the treatment after the first time, I was like, ‘I’ve got an opportunity now. Somebody’s given me an opportunity to do something with my life’. Talking about it, the blogs, little interviews, it’s been helpful to me, but I’ve found that it’s helped other people.”

Lormor, the former Newcastle United forward, is 49 now. Last year, having received the third of four cancer diagnoses, he began writing a blog. He would write in the middle of the night, beset by sleep deprivation and whirring emotions, in an unfiltered and beautifully incisive way. By turns, the blog was heart-wrenching, brutal and laugh-out-loud funny. “Sheffield is a beautiful city,” he wrote in hospital as the grim reality became clearer, “and I’m really looking forward to experiencing the history and culture from my 14th floor window.”

Eight years ago, his mother, Sheila, passed away. He knew she was ill, with ovarian cancer that had spread to her stomach, but she had protected the family from much of the realities. As a father of four, Lormor understands why, but he chose to do it differently when he was told, for the first time, that he had follicular lymphoma. “I just became really open. For years I hid with drinking and stuff like that. I ended up having counselling because of my depression. I spoke to this counsellor and from five sessions she just got my world. It was the first time I’d properly spoken about stuff. I’ll just be brutally honest with people, really, and tell them how it is.”

He remembers waking up in Hasland Ward at Chesterfield Royal Hospital on his 49th birthday, knowing he had to drive to Sheffield later that day to discuss the stem cell transplant he was due to undergo. “If I took that seriously, it would have driven me insane. I was just in a room on my own. I remember writing it myself – there were times I was angry, upset, but other times I just thought, ‘you’ve got to chuck some humour in there’. I was chuckling to myself while I was doing it.

“There seemed to be a big void. You’re diagnosed, then you wait to start treatment. There’s a lot of support out there but at the time I couldn’t find it. I was bouncing off walls – what do I do? How bad is this going to be? I just thought, it might give someone some comfort or understanding.”

It helped and inspired many who read it. Lormor’s father, Tom, saw it too. “People are frightened to ask. They want to ask how you are, but they don’t want the answer to be ‘I’m screwed, I’ve got six weeks to live’,” he says. “My dad’s in his mid-70s, a man’s man. But I know, because I wrote it down, he’s read it. He’ll ring me and say, ‘are you alright?’ ‘Yeah, I’m fine, is everything OK?’ ‘yeah, yeah’, blah, blah. Then we’ll talk about bloke things, like how Newcastle are doing and that.” Maybe that was his way of caring, of acknowledging the gravity of what was happening to his son? “Yeah, it probably was.”

There is a lot to talk about. Lormor lives in Langley Mill, a small town between Nottingham and Derby, and has just got back from a morning gym session. Do you have time? This probably isn’t a conversation to be rushed. “Yes – we might as well do it properly,” he nods. “There’s no point doing it half-arsed.”

-

“I once read about the rocking chair effect. Imagine you’re sat in your rocking chair on your veranda in the twilight of your life and you look back on your life. Make sure you have no regrets. Make sure you have no ‘I wish I had done that’ or ‘I could have done that’ or ‘I wish I could have gone there’, regardless of how big or small they might have been.”

20th August 2019

Anthony Lormor was born in Ashington on 29th October 1970, and moved to Wallsend when he was five. He started playing football for the fabled Wallsend Boys’ Club at eight and had caught Newcastle United’s eye at 12, when he was already six feet tall. After leaving Burnside College he was given an apprenticeship by the club, earning £27.50 a week.

He lived in Battle Hill with his parents and brother, Craig, filling boredom in the summer of 1987 by going out and running. He returned for pre-season in great shape and John Pickering, Willie McFaul’s first team coach, brought him to train with first team at Benwell. Lormor was Anth then, a shy, wiry centre forward, but he “could let everything go” on the pitch. He knew he had a chance.

It was a transitional United team, full of characters; among them, Paul Gascoigne. “All he’d ever say was, ‘all you need to do is just give me the ball. Wherever I am, if you control it, just give me the ball. Don’t worry if there’s somebody on us – you control it, give me the ball and get in the box’,” Lormor recalls. “And that’s all I ever did.”

A young Lormor during his United days

Pickering would keep the young man grounded, denying him a debut against a “far too violent” Wimbledon side the day Vinnie Jones famously acquainted himself with Gascoigne, but in January 1988 he turned a corner. A goal in a friendly thrashing of Queen of the South earned him a debut five days later, as a substitute for Mirandinha in a 2-0 win over Tottenham Hotspur at St. James’ Park.

Lormor remembers the Friday before a home game against Oxford that April, walking into the little hut on the bowling green in Benwell where team meetings would be held. “As we’ve gone in, we’ve seen the flip chart which they had the team on, which they’d then reveal. We’re all sat there, he’s peeled it back and I’m playing up front with Michael O’Neill. I was just like, ‘oh my God’.”

He was told not to tell the press, just to turn up ready to play. The night before he walked from Battle Hill to the shops on the Coast Road, buying a bag of sweets to eat on the way home, completely unburdened by nerves. “I got the bus to the match the next day – from Battle Hill to Eldon Square and walked up to the ground, with my boots in a bag.”

Five minutes in, O’Neill rounded the goalkeeper and clipped it into the six-yard box. There were so many thoughts running through his head. “If I try and volley it and miskick it I’ll never live it down. I just thought, I’ll stick my massive head on it. That’s how the diving header came about.” A goal on his first start. Gascoigne swung from the crossbar as Lormor picked himself out of the net at the Gallowgate End. “And nobody is more delighted than Paul Gascoigne,” noted the commentator, in a typically crackly ‘80s kind of way, “but for, perhaps, Anth Lormor.”

He followed it up with what proved to be the winner at Portsmouth two days later. Pickering wouldn’t let the 17-year-old enjoy a drink on the bus journey home, insisting instead that he spent the long trip north picking up empty tins as the rest of the squad ‘refuelled’ after their final away game of the season.

That summer, a mouthful of sores cost him the chance to go to Sweden with the first team in pre-season. John Hendrie and John Robertson arrived and Lormor was sent on loan to Norwich City. He netted what proved to be his final Newcastle goal against West Ham in May 1989 before being carried off at Old Trafford on the season’s final day. “Steve Bruce landed on me – I went for a diving header and landed on my shoulder and he landed on top of us.”

It was never quite the same for him at his boyhood club. He linked up again with Pickering at Lincoln City in 1990, signing a blank contract for the eccentric Colin Murphy and laying the foundations for a nomadic lower-league career which saw him represent 11 league clubs. A series of knee injuries, including one catastrophic one during a training session at Lincoln, meant he had to change his style but he is remembered with fondness at Sincil Bank and Chesterfield, in particular, having netted in the Spireites’ Division Two play-off final win at Wembley in 1995 “The worst game of my entire career,” he grins, “but I still dine out on that!”

The sport’s culture was changing by the time he hung up his boots at Hartlepool in 2002. He knew he’d had enough and his knee was crumbling. His career was over. “The last year before I finished, they brought in a strength and conditioning coach. He was like an alien. ‘What’s this guy doing here?’” he says, with a hearty laugh. “Weights? I’m not doing weights. We’d finish training in the morning and he’d say, ‘right, we’ve got a weights session this afternoon’. I’m teeing off at half one! No chance.

“I lived in a guest house in Seaton Carew. I went into panic mode. I didn’t know what I was going to do. I drank a lot. I was married at the time – she was living in Lincoln and I was in Hartlepool. We moved back to Newcastle but I was in a right state. I was not a great person, and we ended up splitting up. I moved back to Nottingham and bumped into a guy, who was a big football fan, he knew who I was. He had a window company. I was desperate for a job. I ended up selling double glazing for three years.”

He went on to work at Mansfield, as commercial manager, and Derby County. It was there that his phone rang as he sat at his desk. “It was my mam. She told me she’d been diagnosed with cancer. My world just fell apart. Absolutely fell apart. I reverted back to the drink, and lost interest in everything.”

Sheila endured it for three years. Lormor moved back home to spend some time with her before she passed away. He was diagnosed with depression and, away from his children, his drinking went “off the scale” for six months after her death in 2012. “I got to a stage where I was drinking that much I ended up spewing up, but I was spewing up blood,” he explains. “There was a huge amount of blood in the shower. That was my calling, sort of thing – I’ve got a choice now. I either go down the route of continuing drinking or I do something with my life.”

In the summer of 2014, Chris Turner, his old manager at Hartlepool and by then chief executive at Chesterfield, handed his old frontman the job of kitman. An old Norwich teammate in Paul Cook was in charge at the time. He was just beginning to sort himself out, and stop the drinking, when he noticed a lump on the side of his neck.

-

“And remember, smile at a stranger today, you might just make their day! But don’t get arrested if it’s part of your bail conditions.”

15th October 2019

Initially, it was the size of a pea – never bigger, never smaller, and it never went away. Lormor mentioned it, flippantly, to a physio and a doctor and, while neither seemed too concerned, he was advised to see a GP. He had a scan and turned up for his appointment with the consultant in his Chesterfield training kit.

“The guy went, ‘it’s cancer’. The first thing I thought was, ‘when am I going to die?’ That was the first thing I remember thinking. I’d seen what had happened to my mum. Bloody hell. When am I going to die?”

He rang his dad but couldn’t get through. He dialled Craig’s number and burst into tears down the phone. Here’s the plan, he explained after recomposing himself: whack it with radiotherapy in Sheffield. It worked, too – after four or five sessions, it had gone.

That was when Lormor sat down with the piece of paper. He took 12 months off work, cashed in his life insurance and set about doing the things he’d always wanted to do. Fundraising. Travelling to America. Changing the world. “As a footballer, a lot of it is take, take, take. Can I give something back? I got in touch with a lymphoma charity and said I wanted to raise some money. I signed up to go to the arctic, trained for it, got myself in some good shape, and got some structure back in my life again.” He got a job on a production line just down the road, making ladders. He walked Hadrian’s Wall for charity. He worked with the Dame Kelly Holmes Trust, running programmes in Derby. It was there he told his story for the first time. He stood up and spoke. There was silence, and then tears.

In 2018, it happened again. “I found a lump in my mouth, between my teeth and my jaw in that fleshy bit.” He had it cut out on a Tuesday, and by Wednesday he was in Stoke doing a talk for an National Citizen Service evening, “looking like I’d had a fight with Anthony Joshua.” That winter, another lump was cut out of his neck. It was lymphoma but it hadn’t spread. He switched on the autopilot. “I don’t know if I felt invincible, but I just went, ‘well, I’ve had it twice now, and it’s not killed me yet. I’ll just get on with life’.”

Lormor in June 2019

He remained upbeat, pragmatic, even when the following summer, it returned – this time in the form of severe stomach pains, black stools and internal bleeding. Eventually, a private consultation paid for by the PFA was arranged. “I just walked in, and the first thing he said was, ‘has anyone had stomach cancer in your family?’ I said, ‘well, I think my mam had’. Right then – we’ll put a camera in your stomach and see what’s going on.”

Lormor had a large tumour on the wall of his stomach. He was sent to Derby, put on a drip for three days and told to wait for an appointment around six weeks later. In that time, he went for a routine check-up at Chesterfield Royal. He smiles, even though it mustn’t be easy. This was the point when he began writing the blog. “I went in, sat down, and never left.”

He started chemotherapy the following Monday, the cancer deemed too dangerous to let linger as he waited for his results. He could feel the tumour on his neck moving as pain riddled his stomach. He lost 25 kilograms in a fortnight as the treatment cycle became more intense; six days of chemo, four days off.

The day before his third session, he met his consultant, who asked if everything was alright. “I had no real side-effects from the chemo. She said, ‘oh, the swelling’s gone down a lot in your neck. Have you got any issues?’ I said ‘no, I’ve just got these two little bumps on my neck’.

“She literally just went white. ‘That’s not good, Mr. Lormor’.”

The lymphoma had become highly aggressive. It was serious. Despite the steroids keeping him awake through the night, he remained optimistic. “I was still alive. I was functioning. I got on so well with the staff – they would hook me up to the chemo and I’d walk around the hospital, having my dinner upstairs, wander off and have a coffee.’ He watched MLS games on his iPad in the night, flying through series of Dexter and filling time as best he could while sneaking in Domino’s pizzas and Indian takeaways. Craig had told him to think about going back to the Maldives when all this was done; to focus on that, on how nice that will be. “When I started with depression, I couldn’t see light at the end of the tunnel,” he says. “But when I spoke to people and the counsellor, I could. That was something to aim for – going on holiday, doing normal stuff again, that was the light. You have to dangle a carrot. I would always give myself something to do, something to aim for.”

Lormor joked in his blog in July 2019 that he was once deemed to have had one of the ten worst haircuts at Newcastle United by a fanzine in the late ‘80s. His perm and his bowl cut – which he adorned with blonde streaks – were fashionable, he insists. It is an amusing tale but one which masked his sadness and a deeper recognition. When fine hairs began falling onto his face, he asked his two youngest children, Ashleigh and Emily, to help him shave it off – “right down to the wood,” he wrote. “If you have cancer, and you have chemo, everyone associates it with losing your hair. The issue I had with it, not a massive issue, was that then people knew you were having chemo and you had cancer. People then would look at your differently. My eyebrows didn’t fall out, but everything else did. So I had eyebrows but no hair,” he pauses. “It was just the realisation that you know you have got cancer.”

Last July, Lormor had a Hickman line fitted in his chest, enabling the direct supply of drugs into his system. For 20 hours a day for five days, he was hooked up to a machine which delivered stronger doses of chemotherapy. The four-hour break became a grim wait for the next lot. A 20-minute shower was little respite. If it worked, he was told he would require a stem cell transplant in Sheffield. If it didn’t, he would be given CAR-T, a complex and risky treatment involving the removal and reprogramming of immune system cells. “I look back on photographs and there’s one where I look like Frankenstein. I’ve got no hair, this big square head, this drain coming out of my chest,” he says. “I still felt fairly oblivious, fairly invincible. I still felt I could get through this. I turned it into a challenge. Because I was fairly comfortable, I just felt like I was ticking over, doing what I needed to do. Each day blended into each other. It was like Groundhog Day. You had to grind through it, like the old pre-season days – just getting your head down and putting one foot in front of the other.”

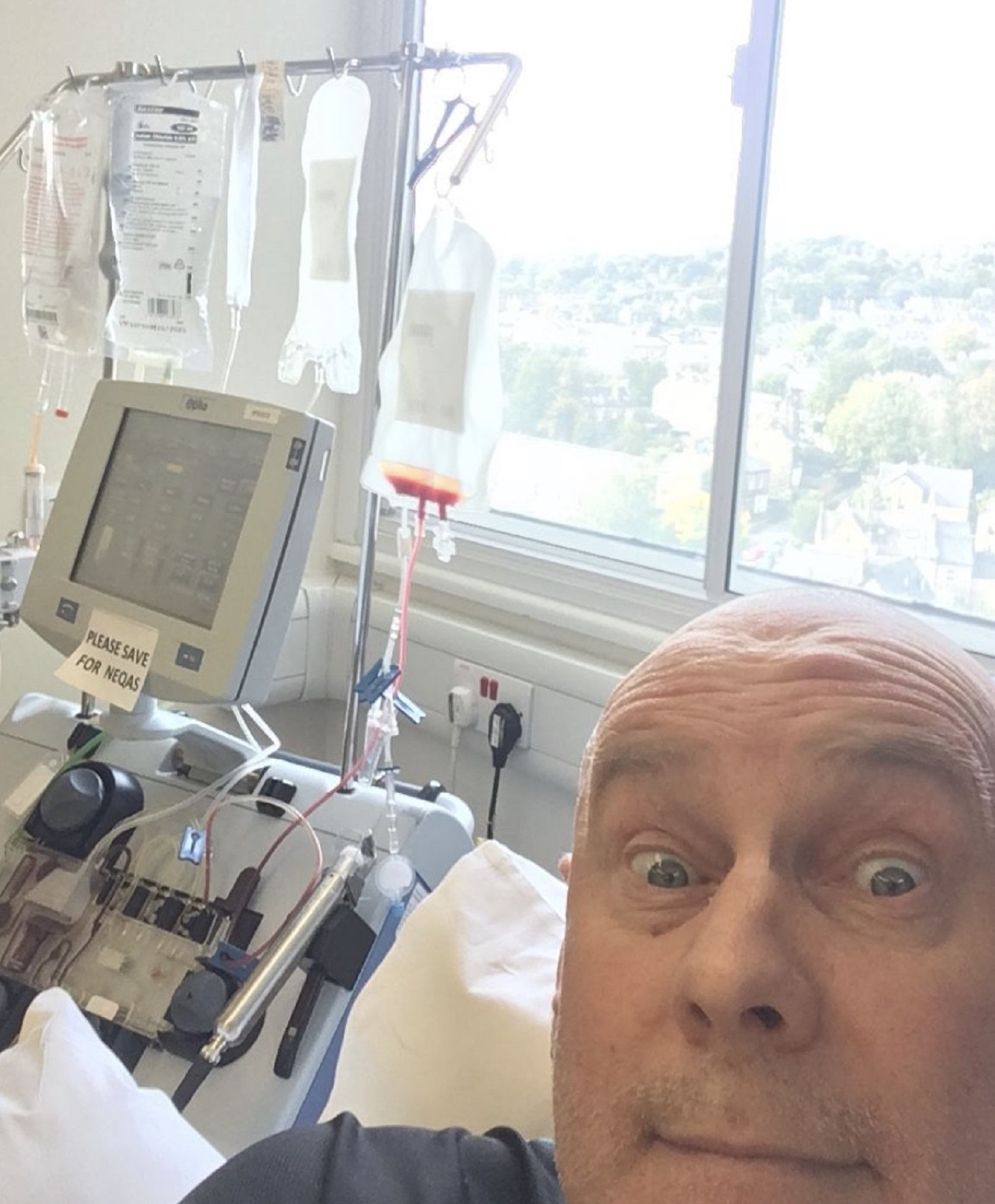

Undergoing treatment in October 2019

The treatment was stabilising but not eliminating the cancer and he knew, by then, that would mean a stem cell transplant. He was sent home from Hasland Ward and told to inject himself twice a day to stimulate the bone marrow and keep his white blood cells at the level required.

His son, Ryan, had graduated from Leeds, and his daughter Ashleigh had celebrated her 14th birthday. He missed out on both. Lormor says he never had his father’s hard edge – he admits that, at first, he even had a fear of needles – but there is a bit of his dad in his make-up. It is an old male trait to not want to show weakness, to not want to let on if you’re scared, but that first trip to the Royal Hallamshire Hospital was a harrowing one. “My first realisation of how things were was when I went to Sheffield. That was a wake-up call. We’re now in a serious situation, you know.” It was the understanding that his chances “were fairly slim, of surviving, really. That’s the God’s honest truth of it. Up until then I’d treated it like a bit of a game. That was the wake-up call. This is pretty heavy stuff, you know.”

He met the consultant, who talked him through the process. “Not sure what's worse, the chemo or having to live in Sheffield?” he joked in the blog. But this was bleak. “At the end he said, ‘with what you’ve got, I’ll be surprised if it works’.” He left the hospital to make the hour’s drive home with his partner, Mel. They didn’t say a word. “We were like two zombies. That was the realisation that this is really serious.”

Process of stem cell harvest took just one day at the start of October. He spent six hours on the machine, with “a funny, salmon-coloured bag of liquid above your head. That’s your stem cells.” He moved into a hospital flat for five weeks and was told to live as normal a life as he could, just two minutes from the front door as his resolve was further tested by some industrial-strength drugs.

The side-effects, which he’d largely escaped to this stage, came swiftly. Lormor remembers being sat on the toilet being violently sick into the sink. When he worsened, he was returned to hospital and put straight into isolation for 14 days. He lost 18 kilos in a fortnight.

It was in P ward, up on the 13th floor, that he reached the lowest point. “I never ate for 14 days, I was fed through a tube. My tongue didn’t fit in my mouth it was that swollen, I had sickness and diarrhoea. A few days into isolation, this nurse came in at 2am to check my bloods and that. I said, ‘have you got anything for us? Can I take a tablet or anything like that?’

“She said, ‘oh, what’s that for?’ I went, ‘I’m done. I want to go to sleep’. She went, ‘what, a sleeping tablet?’

“I said, ‘no, no. Is there anything you can give me? I’ve had enough. I’m done. This has finished me. I want to go to sleep and not wake up’.”

His spirit, so strong for so long, had been steadily chipped away at when that night came around. How did he keep going? “I have to be honest. I don’t know. It’s back to that pre-season thing. One foot in front of the other. You’re just sat watching the clock, and it moves on a second – and then you’re a second closer to hoping that this is going to stop.”

-

“I was only given a 20/30% chance that this would work and it looks like I’ve smashed the **** out of that.”

3rd October 2019

Isolation broke Lormor. He says it scarred him for life. An infection caused by some soil entering his Hickman line as he put away garden furniture complicated things but, on the 7th November, his stem cells were reinserted. A week later he was in his room when the consultant knocked at the door.

“He came in. He said today is the first day your blood count has started to rise. You can go home Saturday,” he remembers. “That was the light at the end of the tunnel – that was my light, you see. I remember him leaving and I was shell-shocked. Me and Mel were just sat there. I burst into tears. ‘It’s over. I’m getting better. I’m going home’.

“I’ve cried at my children being born, but I can’t remember ever crying at much else, apart from the first time I found out (I had cancer). That was just like – bang – floods of tears. I’ve got through it. At the point I would have willingly jumped out of the window, I couldn’t see that light, it was just a dark passage. But this was it. Massive relief.”

His euphoria was put into sharp focus when he discovered that another woman, who was admitted to Sheffield at the same time as him for a stem cell transplant, hadn’t made it. Lormor began sketching out the life he wanted to live. He got back into the gym, managing a 20-minute run on a treadmill, and set his sights on the Great North Run. He got his holiday, heading to Cape Verde to enjoy the sun while he waited for a consultation in Sheffield.

The week before he was due to attend that meeting and find out, definitively, the impact the transplant had had, a letter landed on his doorstep. The stamp indicated it was from Weston Park Hospital. “As soon as I saw the stamp, I knew. Weston Park do radiotherapy.” There was confusion the next day, as he sat quietly while a consultant told him he would need a mask fitted and immediate treatment.

The mask Lormor was fitted with during his final bout of radiotherapy

It transpired that he hadn’t been completely ridded of the wretched disease. There were two further bits of cancer that needed to be addressed. With possibility of CAR-T still persisting, he was told that 15 sessions would be condensed into six.

Before the process started once more, for a fourth time, the consultant back at the Royal Hallamshire Hospital phoned him. He was to be signed off to Weston Park, who would then release him back to Chesterfield Royal. It was one of those calls that sticks in the memory.

“His parting shot was, ‘we will meet again’. I was like, ‘oh, right’. He said, ‘this will come back. We will meet again’. He said, ‘if it comes back as follicular lymphoma, it’s manageable. If it comes back highly aggressive and high-grade, it’s unmanageable’.”

It is a sobering notion but Lormor is attuned to life’s harsh realities. His final PET scan was in August 2020, three months after his last radiotherapy session. Two days later the phone rang. It was a withheld number. His two youngest children, Ashleigh and Emily, were sat with him. His heart sank.

“I asked her three times,” he smiles. “’Honestly? All gone?’

“‘Yes’. That was the confirmation. At the minute, I’m cancer-free.”

The last few weeks have given him time, precious time, to think. “When I first saw the consultant in Sheffield, I went to myself, ‘right – the most probable cause of me dying is going to be this’. I sort of accepted that. But I didn’t let it beat me. I still had the challenges of getting through the treatment.

“The majority of the time, you think, ‘I’ll probably die of this’. But whether that’s tomorrow, or in ten years’ time, I can’t sit around waiting for that day to happen. I’m going to get on with my life, and hopefully bring everybody else along with me. If that day comes, then so be it, you know – but I’m not sitting here waiting for it to come.”

The stakes will begin to change in his favour, he says, on 23rd November 2020 – a year on from his release from hospital. It is remarkable that he has come this far, but there is more to do. Lormor has been camping and playing golf – a local club only charges him for the amount of holes he can manage at the moment (he got to six recently; nine is the next step). He mentions a possible jaunt to Germany, COVID-19 regulations permitting, and he’s always wanted to go to Australia.

“Every morning I’ll wake up, and the missus will say, ‘how are you today?’. Well, I can see the sky, so that’s a bonus. I can look out the window, and I’m not looking at the top of a box,” he jokes, with a chuckle. “I know people could see that as being a bit morbid, but that’s how I’ve got through it.

“And even to this day, I give myself one thing to do every day that gets me out the house. I’ll only do maybe one or two things, but I’ll know tomorrow I have something else to do to get me out, and then the next day. I’ve got a little calendar to put things on. I always have something to plan for, always something to look forward to, but also a realisation that I can get up and do something.”

We have been talking for over four hours. Mel will be home from work later and there is shopping to be done. For now, life continues. Next month, Lormor will celebrate his 50th birthday. The Great North Run might even be back on the cards next year, if all goes to plan. “Never mind being fit enough – if I’m still alive in 12 months’ time I’ll be chuffed to bits!” He laughs. And, when you know what he has been through just to be here, it is hard not to laugh with him.